“We can live the stories or hear about them later from others. I choose the former.” – Charlie Sheen’s declaration of narrative reclamation

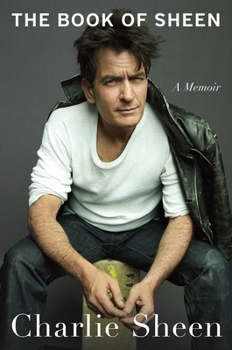

What happens when Hollywood’s most infamous bad boy—a man who once earned $1.8 million per episode before spectacularly imploding on national television—decides to tell his own story after eight years of sobriety? In his unflinching memoir The Book of Sheen, actor Charlie Sheen offers something increasingly rare in celebrity tell-alls: an unfiltered account that refuses the comforting arc of redemption narratives. Published in September 2025, eight years after his final attempt at sobriety, the 359-page memoir chronicles a life that begins with near-death by umbilical strangulation and careens through decades of excess—a journey Sheen frames not as cautionary tale but as raw testimony of survival.

Sheen’s narrative spans his childhood as the son of Martin Sheen, including months spent on the chaotic set of Apocalypse Now in the Philippines, through his rise as an 1980s heartthrob in films like Platoon and Wall Street, to his eventual reign as television’s highest-paid actor on Two and a Half Men. But the book’s real subject isn’t career milestones—it’s the constant undercurrent of addiction that shaped every choice, every relationship, every spectacular rise and catastrophic fall. From smoking his first joint at age eleven with childhood friend Chris Penn to his introduction to crack cocaine in 1992, Sheen meticulously documents his relationship with substances with the precision of someone who understands he survived something that should have killed him multiple times over.

What makes Sheen’s approach particularly notable is his explicit rejection of conventional recovery narratives. While the final pages address his eight years of sobriety—undertaken for his children and grandchildren—most of the memoir dwells in what he calls his “exhaustive and sometimes exhausting survey of life on the edge.” He dismisses Alcoholics Anonymous as “medieval gibberish club” while praising sex workers for providing “a convenience-tax for a guaranteed outcome the other dating scenarios couldn’t offer.” This isn’t the sanitized confession of a repentant celebrity seeking public absolution; it’s something messier and more honest—a man accounting for his choices without necessarily apologizing for all of them. As Sheen himself notes, “Forgiveness is still an evolving thing,” marked by what he calls “shame shivers”—moments of heinous memories that are “getting farther in between.”

Rather than offering redemption, Sheen presents a portrait of addiction as his life’s constant companion—from the 1980s and 90s filled with alcohol and hard drugs, through explosive divorces, his HIV diagnosis, and assault allegations that dominated tabloids for decades. The book forces uncomfortable questions about celebrity, accountability, and the limits of public forgiveness. This is the same man who, in 2011, ranted on national television about “tiger blood” and “Adonis DNA,” claiming to be “bi-winning” while attributing his behavior to testosterone cream rather than relapse. Now, with the perspective of eight years of sobriety, he offers neither full contrition nor complete justification—just the messy, complicated reality of someone who has spent six decades learning to live with himself.

The memoir raises thorny questions about what we expect from celebrity confessionals and whether genuine accountability requires the performance of redemption. Sheen’s three marriages appear and vanish from the narrative with startling speed, his relationships treated more as collateral damage than meaningful connections requiring deep reflection. This isn’t necessarily dishonesty—it may be the most honest thing in the book, an admission that for decades, other people were secondary to the primary relationship with substances and chaos. The question isn’t whether Sheen has learned his lessons or become a better person; it’s whether we can stomach a memoir that refuses to package its horrors in the comforting language of transformation.

Are we prepared to accept addiction memoirs that don’t follow the familiar arc from rock bottom to enlightenment? And more fundamentally, when someone has caused real harm to real people over decades—but survived when many didn’t—what do we actually want from their story?

“The question isn’t whether Charlie Sheen deserves redemption—it’s whether the rest of us are ready to confront the uncomfortable truth that survival and transformation aren’t always the same thing.”